New York, Metropolitan Opera, Season 2018-19

“MEFISTOFELE”

Opera in prologue, four acts and epilogue. Libretto by the composer, based on the play Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Music by Arrigo Boito

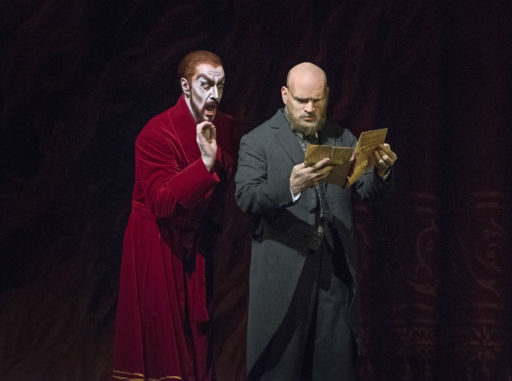

Mefistofele CHRISTIAN VAN HORN

Faust MICHAEL FABIANO

Wagner RAÚL MELO

Margherita ANGELA MEADE

Marta THEODORA HANSLOWE

Elena JENNIFER CHECK

Pantalis SAMANTHA HANKEY (debut)

Nereo EDUARDO VALDES

Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera

Conductor Carlo Rizzi

Chorus Master Donald Palumbo

Production Robert Carsen

Sets and Costumes Michael Levine

Lighting Duane Schuler

Choreographer Alphonse Poulin

Revival stage director Paula Suozzi

Production co-owned by the San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera

New York, 8 November 2018

Arrigo Boito is like Berlioz in his resistance to, his lack of interest in, the style and trends of his own era, and Boito’s masterpiece, Mefistofele, is like Berlioz’ gaudier creations, enormous, ingenious and odd, offering little compromise to the unsympathetic. Mefistofele is a grand opera without the grandstanding showpieces typical of the genre, a serious attempt by a seriously intellectual composer to create a music-drama out of Goethe’s Faust, of which Part II was then newly published and not yet music’d by anyone. Boito called upon grand forces in his orchestra, chorus, dancers and designers, and topped it with one of the great basso cantante roles of all time. And yet the music is not lovable, or at any rate not widely loved. The effects are witty or bombastic by turns, and Margherita’s brief mad scene is deeply affecting in the hands of a great singing actress. In the proper hands, with the proper artists, Mefistofele makes a spectacular effect—the Tito Capobianco production for the old New York City Opera was one of the things that put New York’s “second” company on the international map, giving notice that they could play hardball with the big boys. But with a less than spectacular cast, even as splendid a production as the one Robert Carsen designed for the San Francisco Opera, and which has returned to the Metropolitan for the first time in many years, the opera is a patchwork quilt that fails to cover its ample body.

Arrigo Boito is like Berlioz in his resistance to, his lack of interest in, the style and trends of his own era, and Boito’s masterpiece, Mefistofele, is like Berlioz’ gaudier creations, enormous, ingenious and odd, offering little compromise to the unsympathetic. Mefistofele is a grand opera without the grandstanding showpieces typical of the genre, a serious attempt by a seriously intellectual composer to create a music-drama out of Goethe’s Faust, of which Part II was then newly published and not yet music’d by anyone. Boito called upon grand forces in his orchestra, chorus, dancers and designers, and topped it with one of the great basso cantante roles of all time. And yet the music is not lovable, or at any rate not widely loved. The effects are witty or bombastic by turns, and Margherita’s brief mad scene is deeply affecting in the hands of a great singing actress. In the proper hands, with the proper artists, Mefistofele makes a spectacular effect—the Tito Capobianco production for the old New York City Opera was one of the things that put New York’s “second” company on the international map, giving notice that they could play hardball with the big boys. But with a less than spectacular cast, even as splendid a production as the one Robert Carsen designed for the San Francisco Opera, and which has returned to the Metropolitan for the first time in many years, the opera is a patchwork quilt that fails to cover its ample body.

It is a great occasion that the Met has brought back this wonderful, imaginative production. Carsen sees Faust’s world as a vast baroque theater. Angels inhabit theater boxes. Processions are borne through the streets as in a religious mystery play, and their themes (Adam and Eve) are mimicked in the seduction of Margherita by Faust. The passing of time is a small turntable with apple trees and, later, barren trees and cobwebs. The witches’ sabbath is an underwear fetish party. The classical sabbath is a ballet divertimento. Helen of Troy a nineteenth-century prima donna, given roses by adoring vassals in black tie. The one concession to the standards of 2018 is to have Mefistofele bare to the waist, even when wearing a floor-length red cape and gloves. It looks sumptuous and has been sumptuously directed and choreographed, and the chorus sing like angels when playing devils or angels, peasants or gods.

production. Carsen sees Faust’s world as a vast baroque theater. Angels inhabit theater boxes. Processions are borne through the streets as in a religious mystery play, and their themes (Adam and Eve) are mimicked in the seduction of Margherita by Faust. The passing of time is a small turntable with apple trees and, later, barren trees and cobwebs. The witches’ sabbath is an underwear fetish party. The classical sabbath is a ballet divertimento. Helen of Troy a nineteenth-century prima donna, given roses by adoring vassals in black tie. The one concession to the standards of 2018 is to have Mefistofele bare to the waist, even when wearing a floor-length red cape and gloves. It looks sumptuous and has been sumptuously directed and choreographed, and the chorus sing like angels when playing devils or angels, peasants or gods.

But all this is mere setting for a cast of vocal soloists who simply aren’t up to the work. Mefistofele, rich as it is in dramatic set pieces and choral and orchestral scenery, is far enough from the mainstream of tuneful pleasure that it does not really land unless performed by the sort of brilliant star singer who can give the material an extra edge. In the title role, you need a Chaliapin or a Siepi—in more recent times, a Treigle, a Ramey, a Furlanetto. Tebaldi, Caballé and, in these parts, Cruz-Romo and Swenson were renowned for the double-role of Margherita and Elena. Suave tenors like Domingo have won plaudits as Faust.

Christian Van Horn is tall, not unimpressive when half-naked, full of panache in the most dazzling of roles—but his pleasing, grainy light bass does not resound through the auditorium. The infernal realms and the shattering principles of the world are not in question. He can toy with us, and with a dining hall full of medieval witches, but he can’t make us feel that the vaults of the depths of the earth are backing him up. He is a performer of great ability and charm but not superhuman. Michael Fabiano, as so often, is very loud when loud music is called for but lacks grace or line when Faust is supposed to woo or ponder or simply be thoughtful. He is a shouting tenor, and an ardent performer; the size of his voice is a pleasure, but he doesn’t seem aware of any other level. Angela Meade, who is not always a convincing actress, is surprisingly effective as Margherita, and it is a relief to hear her sing coloratura to the purpose (in “L’altra notte”) rather than tossed about aimlessly like wildflowers in a storm, her usual method. Even so, her top notes were buzzy, not single true notes ringing out as desperate prayers or cries of enlightenment. She eschewed the double role of Margherita-Elena, leaving the latter to Jennifer Check, who sang it ineffectively. Theodora Hanslowe, a house regular, sang neighbor Marta and was, as always, a pleasure to hear.

Christian Van Horn is tall, not unimpressive when half-naked, full of panache in the most dazzling of roles—but his pleasing, grainy light bass does not resound through the auditorium. The infernal realms and the shattering principles of the world are not in question. He can toy with us, and with a dining hall full of medieval witches, but he can’t make us feel that the vaults of the depths of the earth are backing him up. He is a performer of great ability and charm but not superhuman. Michael Fabiano, as so often, is very loud when loud music is called for but lacks grace or line when Faust is supposed to woo or ponder or simply be thoughtful. He is a shouting tenor, and an ardent performer; the size of his voice is a pleasure, but he doesn’t seem aware of any other level. Angela Meade, who is not always a convincing actress, is surprisingly effective as Margherita, and it is a relief to hear her sing coloratura to the purpose (in “L’altra notte”) rather than tossed about aimlessly like wildflowers in a storm, her usual method. Even so, her top notes were buzzy, not single true notes ringing out as desperate prayers or cries of enlightenment. She eschewed the double role of Margherita-Elena, leaving the latter to Jennifer Check, who sang it ineffectively. Theodora Hanslowe, a house regular, sang neighbor Marta and was, as always, a pleasure to hear.

So much of Mefistofele is choral in its grandeurs and its special effects—the opera simply cannot be given without major work from this department, and the Met’s eager and enormous chorus was clearly delighted to go to town on it, from cherubs to carnival celebrations to witches’ sabbath orgiasts. This is an opera where having such forces to work with really pays off. Carlo Rizzi held the diverse battalions at his command in remarkable order; Boito’s intricate effects glowed into the auditorium. I do think Samantha Hankey, the debutante as harp-strumming Pantelis, might figure out how to strum in sync with the very simple chords produced by the harp in the orchestra pit. There can’t be many shows in town, at the Met or anywhere else, that produce as many megatheatrical effects as this one does, from the thoughtful orchestration to the choral thunder to the inspiring special effects. You almost believe creation and the risk of the soul matter. Photo Karen Almond