Sydney. Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House. Opera Australia 2018 Season.

“THE MERRY WIDOW” (Die Lustige Witwe)

Operetta in three acts, Libretto by Victor Leon and Leo Stein. English translation Justin Fleming.

Music by Franz Lehár

Hanna Glavari DANIELLE DE NIESE

Danilo Danilovich ALEXANDER LEWIS

Baron Mirko Zeta DAVID WHITNEY

Valenciennes, his wife STACEY ALLEAUME

Camille de Rosillon JOHN LONGMUIR

Njegus BENJAMIN RASHEED

Alexis Kromov RICHARD ANDERSON

Olga Kromov AGNES SARKIS

Dominic Bogdanovich STUART HAYCOCK

Sylvaine, his wife CELESTE LAZARENKO

Raoul De St. Brioche BRAD COOPER

Viscount Nicolas Cascada LUKE GABBEDY

Konrad Pritschisch TOM HAMILTON

Praskovia, his wife DOMINICA MATTHEWS

Opera Australia Orchestra and Chorus

Conductor Vanessa Scammell

Chorus Master Anthony Hunt

Director and Choreographer Graeme Murphy

Associate Director/Choreographer Janet Vernon

Set Designer Michael Scott-Mitchell

Costume Designer Jennifer Irwin

Lighting Designer Damien Cooper

Sound Designer Tony David Cray

Sydney. 5th January, 2018.

Opera Australia has returned to a renovated Sydney Opera House stage and pit, welcoming in 2018 on a festive and bubbly note with an ebullient new production of The Merry Widow. There was great anticipation for the first professional appearance in Australia of Danielle de Niese, in the title role. Born in Melbourne, she spent her childhood there before moving to the States and pursuing an international career. The gala performance on 5th January was packed with a very responsive and appreciative audience. The evening got off to a lively start with an explosive ouverture taken at a strapping pace by the conductor Vanessa Scammell, setting the tone of the performance. The impact of the production was definitely of a show or musical rather than that of a traditional operetta. All characters were mic’d both for the singing and for the dialogue, which levelled out any attempt at colour or nuance. The effect was overwhelming, emphasised by the fact that the orchestra was inaudible, manipulated technologically just to supply a

Opera Australia has returned to a renovated Sydney Opera House stage and pit, welcoming in 2018 on a festive and bubbly note with an ebullient new production of The Merry Widow. There was great anticipation for the first professional appearance in Australia of Danielle de Niese, in the title role. Born in Melbourne, she spent her childhood there before moving to the States and pursuing an international career. The gala performance on 5th January was packed with a very responsive and appreciative audience. The evening got off to a lively start with an explosive ouverture taken at a strapping pace by the conductor Vanessa Scammell, setting the tone of the performance. The impact of the production was definitely of a show or musical rather than that of a traditional operetta. All characters were mic’d both for the singing and for the dialogue, which levelled out any attempt at colour or nuance. The effect was overwhelming, emphasised by the fact that the orchestra was inaudible, manipulated technologically just to supply a bland and expressionless accompaniment. Key moments when the violin and cello solos should be in strong relief, to express what the two lovers cannot say in words, were as faint as a distant memory. The contrasts intrinsic to Lehár’s orchestration filled with well-defined colour and harmony of the songs, duets, waltzes, marches, gallops, can-cans and polonaises were sadly not in relief. The clever English translation by Justin Fleming was a joy. He has made the libretto vivacious and appealing by updating it, taking entertaining and cute liberties along the way. However he still manages to embrace and communicate the sense and style of the original version. The set designer Michael Scott Mitchell and the costume

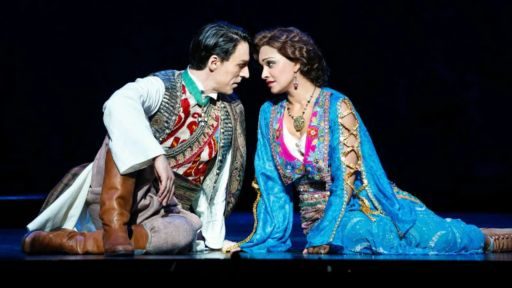

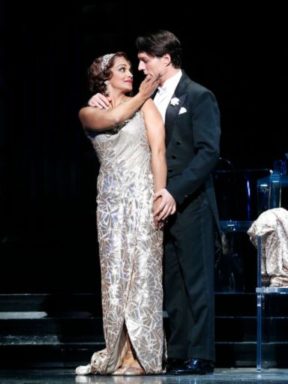

bland and expressionless accompaniment. Key moments when the violin and cello solos should be in strong relief, to express what the two lovers cannot say in words, were as faint as a distant memory. The contrasts intrinsic to Lehár’s orchestration filled with well-defined colour and harmony of the songs, duets, waltzes, marches, gallops, can-cans and polonaises were sadly not in relief. The clever English translation by Justin Fleming was a joy. He has made the libretto vivacious and appealing by updating it, taking entertaining and cute liberties along the way. However he still manages to embrace and communicate the sense and style of the original version. The set designer Michael Scott Mitchell and the costume  designer Jennifer Irwin followed suit by shifting the era forward by about 20 years to the 1920s and capitalising on the traits that made the 20s roaring. The opulent satin evening gowns cut on the bias were slinky and flirtatious, in line with the behaviour of just about every female in the piece. The men’s attire was distinguished and beautifully tailored, the grisettes costumes were sumptuously sparkling, and the second act national costumes were rich and elegant. The set design took advantage of the 20s framework to inject a sense of innovation and modernity, drawing it closer to 21st century sensibilities. The Art Deco bronze geometric lattice screens in the Pontevedrin embassy in the first act gave the impression of avant garde chic and provided a sense of depth and space to the insurmountable problem of the punishingly tiny stage of the opera theatre. What should have been a stunning reference to Monet’s water lily murals, the evocative and beautifully appropriate backdrop representing Hannah’s Parisian garden in the second act, seemed crammed. The sensation of space and fluidity of movement owe everything to Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon’s vivacious and elegant direction and choreography. The characters and chorus enter, exit, move, cross, interact and pose with ease, free from stagey or awkward moments. The dance numbers are delightful and entertaining, particularly the drink waiters’, but owing to the limited stage space, the traditional folk dance seemed conspicuously compact. The final act can-cans were provocatively modern and uninhibited with a touch of the burlesque, raising the bar of risqué to contemporary relevance. Damien Cooper’s lighting enhanced the staging throughout, highlighting the luxurious textures of the costume fabrics, enriching the sets and flattering the protagonists. In the first act, his lighting gave the bronze lattice work texture, weight and gleam, and subtle modulations in atmosphere substantiated the mood shifts in the plot. The luminous early evening of the garden scene with the beautiful Monet inspired backdrop and the lively national dances slowly transformed into the subtle allure of the glowing and darkening pavilion scene, and in the last act the grisettes’ can-can was an explosion of light which seemed to ignite the colour of their costumes. The

designer Jennifer Irwin followed suit by shifting the era forward by about 20 years to the 1920s and capitalising on the traits that made the 20s roaring. The opulent satin evening gowns cut on the bias were slinky and flirtatious, in line with the behaviour of just about every female in the piece. The men’s attire was distinguished and beautifully tailored, the grisettes costumes were sumptuously sparkling, and the second act national costumes were rich and elegant. The set design took advantage of the 20s framework to inject a sense of innovation and modernity, drawing it closer to 21st century sensibilities. The Art Deco bronze geometric lattice screens in the Pontevedrin embassy in the first act gave the impression of avant garde chic and provided a sense of depth and space to the insurmountable problem of the punishingly tiny stage of the opera theatre. What should have been a stunning reference to Monet’s water lily murals, the evocative and beautifully appropriate backdrop representing Hannah’s Parisian garden in the second act, seemed crammed. The sensation of space and fluidity of movement owe everything to Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon’s vivacious and elegant direction and choreography. The characters and chorus enter, exit, move, cross, interact and pose with ease, free from stagey or awkward moments. The dance numbers are delightful and entertaining, particularly the drink waiters’, but owing to the limited stage space, the traditional folk dance seemed conspicuously compact. The final act can-cans were provocatively modern and uninhibited with a touch of the burlesque, raising the bar of risqué to contemporary relevance. Damien Cooper’s lighting enhanced the staging throughout, highlighting the luxurious textures of the costume fabrics, enriching the sets and flattering the protagonists. In the first act, his lighting gave the bronze lattice work texture, weight and gleam, and subtle modulations in atmosphere substantiated the mood shifts in the plot. The luminous early evening of the garden scene with the beautiful Monet inspired backdrop and the lively national dances slowly transformed into the subtle allure of the glowing and darkening pavilion scene, and in the last act the grisettes’ can-can was an explosion of light which seemed to ignite the colour of their costumes. The production relies on a fine cast of singers. Clean diction and firm emission was a hallmark of the performance and a sine qua non for amplified singing. Danielle de Niese was a feisty and energetic widow showing all the character of her original farm girl self. A skilled dancer, de Niese held her own amongst the dancers and shone. Her spoken and vocal delivery was strong and direct. This seemed at times to be dictated by the amplification which was an obstacle to any attempt at delicate piano singing, particularly apparent in her arietta Vilja. The generous voice, bright ringing vocal quality and legato phrasing of John Longmuir in the role of Camille put the sound system to its test. The vocal range and type of music of the other singers was more conducive to amplification and provided appropriate support. Alexander Lewis was a youthful

production relies on a fine cast of singers. Clean diction and firm emission was a hallmark of the performance and a sine qua non for amplified singing. Danielle de Niese was a feisty and energetic widow showing all the character of her original farm girl self. A skilled dancer, de Niese held her own amongst the dancers and shone. Her spoken and vocal delivery was strong and direct. This seemed at times to be dictated by the amplification which was an obstacle to any attempt at delicate piano singing, particularly apparent in her arietta Vilja. The generous voice, bright ringing vocal quality and legato phrasing of John Longmuir in the role of Camille put the sound system to its test. The vocal range and type of music of the other singers was more conducive to amplification and provided appropriate support. Alexander Lewis was a youthful  Danilo perhaps lacking the weight of years on his shoulders. Nevertheless he sang and acted with style and grace. Stacey Alleume was an enchanting Valencienne although her character was perhaps the least defined of the production. Perhaps some extra body language was needed to indicate clearly that her real attachment was to her husband and that her infatuation with Camille, while sincere, was an escapade.The one purely acting role of Baron Mirko Zeta played by David Whitney was honed to perfection. He managed to present the Baron as a credible character avoiding portraying him as a fool in an overtly theatrical manner, as he blindly ignores all damning evidence of his wife’s compromising behaviour. His quietly stunned realization of the fact that he has cut a foolish figure genuinely aroused the audience’s heartfelt sympathy. A poised and well balanced portrayal of Njegus by Benjamin Rasheed brought the right dose of dryness and wit to the proceedings before stealing the show with an uproarious song and dance act with, unknowingly, a transvestite. The other couples involved in the various misunderstandings and intrigues woven into the plot, Alexis and Olga Kromov played by Richard Anderson and Agnes Sarkis, Dominic Bogdanovich and his wife Sylvaine, played by Stuart Haycock and Celeste Lazarenko, and Konrad Pritschisch and his wife Praskovia played by Tom Hamilton and Dominica Matthews, were well defined and convincing. Brad Cooper and Luke Gabbedy as Raoul de St. Brioche and Viscount Nicolas Cascada completed the cast. The chorus under the direction of Anthony Hunt sang and acted with their customary energy and professionalism as did the dancers. The production runs until the beginning of February for an astonishing total of 34 performances. Photo by Jeff Busby

Danilo perhaps lacking the weight of years on his shoulders. Nevertheless he sang and acted with style and grace. Stacey Alleume was an enchanting Valencienne although her character was perhaps the least defined of the production. Perhaps some extra body language was needed to indicate clearly that her real attachment was to her husband and that her infatuation with Camille, while sincere, was an escapade.The one purely acting role of Baron Mirko Zeta played by David Whitney was honed to perfection. He managed to present the Baron as a credible character avoiding portraying him as a fool in an overtly theatrical manner, as he blindly ignores all damning evidence of his wife’s compromising behaviour. His quietly stunned realization of the fact that he has cut a foolish figure genuinely aroused the audience’s heartfelt sympathy. A poised and well balanced portrayal of Njegus by Benjamin Rasheed brought the right dose of dryness and wit to the proceedings before stealing the show with an uproarious song and dance act with, unknowingly, a transvestite. The other couples involved in the various misunderstandings and intrigues woven into the plot, Alexis and Olga Kromov played by Richard Anderson and Agnes Sarkis, Dominic Bogdanovich and his wife Sylvaine, played by Stuart Haycock and Celeste Lazarenko, and Konrad Pritschisch and his wife Praskovia played by Tom Hamilton and Dominica Matthews, were well defined and convincing. Brad Cooper and Luke Gabbedy as Raoul de St. Brioche and Viscount Nicolas Cascada completed the cast. The chorus under the direction of Anthony Hunt sang and acted with their customary energy and professionalism as did the dancers. The production runs until the beginning of February for an astonishing total of 34 performances. Photo by Jeff Busby