Chicago, LOC, season 2017 /2018

“DIE WALKÜRE”

Music drama in three acts, libretto by the composer.

Music by Richard Wagner

Wotan ERIC OWENS

Fricka TANJA ARIANE BAUMGARTNER

Brünnhilde CHRISTINE GOERKE

Siegmund BRANDON JOVANOVICH

Sieglinde ELISABET SWID

Hunding AIN ANGER

Gerhilde WHITNEY MORRISON

Helmwige ALEXANDRA LoBIANCO

Waltraute CAHTERINE MARTIN

Schwertleite LAUREN DECKER

Ortlinde LAURA WILDE

Siegrune DEBORAH NANSTEEL

Grimgerde ZANDA SVEDE

Rossweise LINDSAY AMMANN

Lyric Opera of Chicago Orchestra

Conductor Sir Andrew Davis

Production David Pountney

Original scenery designs by Johan Engels

Scenery designed by Robert Innes Hopkins

Costumes Marie-Jeanne Lecca

Lighting Fabrice Kebour

Choreography Denni Sayers

Fight Director Chuck Coyl

Chicago, 18 November, 2017

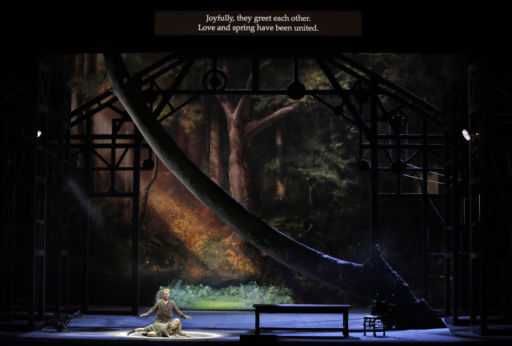

The Lyric Opera of Chicago began its new Ring of the Nibelungs last season with a well-received pre-French Revolution-looking Das Rheingold. This season, producer David Pountney has set Die Walküre in the Industrial Revolution: Hunding’s home a brick-walled factory loft with a tree snaking through it (Sieglinde is chained to the tree), Wotan’s study a High Victorian pilastered parlor, Valkyrie Rock a blood-spackled field hospital such as Florence Nightingale might have deplored. The costumes pursue this lead, putting Siegmund in a Pickwickian waistcoat over shirtsleeves, Wotan and Brünnhilde in formal attire, Fricka in a handsome raspberry suit, and a horde of mourners with top hats and dark wreaths for the Announcement of Death. Brünnhilde enters Siegmund’s uneasy dreams mounted on a flying horse (stage “actors” wheel this curious machine), and predicts his demise over her shoulder. The valkyries are reduced by Wotan’s wrath to schoolgirls in baby chairs. (Their hospital having vanished.) Brünnhilde is stalked by a gang of creepy customers in trench coats when Wotan tells her of her fate to marry humans. Fire is an athletic dancer spinning about in a black box against a background film of flames, while Brünnhilde lies asleep on its roof. All this creates a tidy backdrop for the dramatic confrontations that are the substance of Wagner’s drama, but one does wish Pountney would not insert dramatic actions that Wagner has not called for: the Norns during the opening storm, the leaping hounds summoned by their namesake Hunding in Act II, those guys in trench coats. These actions do not always correspond with the themes being played by the orchestra at such moments; they jar the sensibilities of those familiar with the score and its meaning. Wagner intended stage action to reflect and coincide with the music as much as possible; symbolic movement may be more ideal for this than too-specific references.

The Lyric Opera of Chicago began its new Ring of the Nibelungs last season with a well-received pre-French Revolution-looking Das Rheingold. This season, producer David Pountney has set Die Walküre in the Industrial Revolution: Hunding’s home a brick-walled factory loft with a tree snaking through it (Sieglinde is chained to the tree), Wotan’s study a High Victorian pilastered parlor, Valkyrie Rock a blood-spackled field hospital such as Florence Nightingale might have deplored. The costumes pursue this lead, putting Siegmund in a Pickwickian waistcoat over shirtsleeves, Wotan and Brünnhilde in formal attire, Fricka in a handsome raspberry suit, and a horde of mourners with top hats and dark wreaths for the Announcement of Death. Brünnhilde enters Siegmund’s uneasy dreams mounted on a flying horse (stage “actors” wheel this curious machine), and predicts his demise over her shoulder. The valkyries are reduced by Wotan’s wrath to schoolgirls in baby chairs. (Their hospital having vanished.) Brünnhilde is stalked by a gang of creepy customers in trench coats when Wotan tells her of her fate to marry humans. Fire is an athletic dancer spinning about in a black box against a background film of flames, while Brünnhilde lies asleep on its roof. All this creates a tidy backdrop for the dramatic confrontations that are the substance of Wagner’s drama, but one does wish Pountney would not insert dramatic actions that Wagner has not called for: the Norns during the opening storm, the leaping hounds summoned by their namesake Hunding in Act II, those guys in trench coats. These actions do not always correspond with the themes being played by the orchestra at such moments; they jar the sensibilities of those familiar with the score and its meaning. Wagner intended stage action to reflect and coincide with the music as much as possible; symbolic movement may be more ideal for this than too-specific references.

Here is what I mean by too much specificity: One of Wagner’s intrusions into the story that he found in the sagas is the Todesverkündingung. There is no reason, actually, that Brünnhilde should appear to Siegmund (valkyries do not appear to anyone else), once Fricka has secured Wotan’s agreement to the hero’s death, except that Wagner wanted to guide us into her decision to revolt. He does this by means of an Aeschylean dialogue, a scene where we understand the statements at cross purposes of characters who do not understand each other. Brünnhilde, hitherto a demigoddess, her father’s alter ego, with no comprehension of human existence, understands the loneliness and courage of mortal existence through her sympathy for Siegmund. It is at this moment that Brünnhilde understands humanity and, in comprehending it, sheds her godhead becomes mortal herself, though she does not realize this. (And as G.B. Shaw pointed out, in The Perfect Wagnerite, to be human, with a living soul, is greater than godhead.) She resolves to defy Wotan and, in fact, has become that defiant individual who will save the world from Wotan’s mistakes—the destiny Wotan intended for Siegmund. It is the pivotal point of the entire Ring.

the sagas is the Todesverkündingung. There is no reason, actually, that Brünnhilde should appear to Siegmund (valkyries do not appear to anyone else), once Fricka has secured Wotan’s agreement to the hero’s death, except that Wagner wanted to guide us into her decision to revolt. He does this by means of an Aeschylean dialogue, a scene where we understand the statements at cross purposes of characters who do not understand each other. Brünnhilde, hitherto a demigoddess, her father’s alter ego, with no comprehension of human existence, understands the loneliness and courage of mortal existence through her sympathy for Siegmund. It is at this moment that Brünnhilde understands humanity and, in comprehending it, sheds her godhead becomes mortal herself, though she does not realize this. (And as G.B. Shaw pointed out, in The Perfect Wagnerite, to be human, with a living soul, is greater than godhead.) She resolves to defy Wotan and, in fact, has become that defiant individual who will save the world from Wotan’s mistakes—the destiny Wotan intended for Siegmund. It is the pivotal point of the entire Ring.

Pountney’s staging begins with Siegmund, visibly asleep, dreaming the whole encounter, the woman flying by on a winged horse. But if the vision is Siegmund’s subconscious speaking, it answers certain questions … and raises others. He has no idea, to begin with, who Brünnhilde is (we know, of course), and no idea why her decision to change sides, to defy Wotan is such a big deal—or, for that matter, why he should trust her. Jovanovich, gradually waking up, and Goerke, having a monumental change of heart in an awkward, mounted position (even, for a moment, poised over the orchestra as if in flight above the theater) portray this concept ardently, their vocalism unimpaired. But it puts us into a puzzle: Are we still in Siegmund’s dream as he charges off to battle or have we awakened? And if he’s awake, why is he still seeing a woman on a flying horse and a funeral procession? The staging seems, at such a point (and it is a very important point in the drama), to be more of a collection of images than something thought through.

Pountney’s staging begins with Siegmund, visibly asleep, dreaming the whole encounter, the woman flying by on a winged horse. But if the vision is Siegmund’s subconscious speaking, it answers certain questions … and raises others. He has no idea, to begin with, who Brünnhilde is (we know, of course), and no idea why her decision to change sides, to defy Wotan is such a big deal—or, for that matter, why he should trust her. Jovanovich, gradually waking up, and Goerke, having a monumental change of heart in an awkward, mounted position (even, for a moment, poised over the orchestra as if in flight above the theater) portray this concept ardently, their vocalism unimpaired. But it puts us into a puzzle: Are we still in Siegmund’s dream as he charges off to battle or have we awakened? And if he’s awake, why is he still seeing a woman on a flying horse and a funeral procession? The staging seems, at such a point (and it is a very important point in the drama), to be more of a collection of images than something thought through.

The international cast assembled by LOC is admirable, across the board. To fill a house the size of the Lyric Opera is extraordinary enough; to do so with such musicality would be thrilling for any company. Christine Goerke has become America’s dramatic soprano, with a near-monopoly on Brünnhilde in our major opera houses. She sang Cassandra at LOC in last year’s triumphant Les Troyens and has sung Turandot, Elektra and the Dyer’s Wife with equal success. The smoothness and glamour of her voice are comparable to its great size, and she can produce it on horseback or on her knees supplicating Wotan. The voice shines over the orchestra without losing its warmth. She is a supple actress, and portrays a tender Brünnhilde, sentimental about the twin lovers even before Siegmund has convinced her to defend them, far more timid than is usual when Wotan outlines her future as a mortal woman. Vocalism aside, the demigoddess was not her style, at least in Pountney’s conception. Eric Owens has graduated from Alberich to Wotan (schwarz-Alberich to licht-Alberich, one might say), and while not as imperial in scope as some Wotans, he compensates in his moments of brooding or uneasy reflecting, in which his dramatic choices are always of interest. It is a thoughtful, appealing performance, full of regret. Tanja Ariane Baumgartner’s ravishing low tones match him with a queenly, sympathetic Fricka, more distressed by Wotan’s clumsy plotting than outraged by his infidelity. The lovers are Brandon Jovanovich, whose dark tenor sound and anguished acting make him a most sympathetic Siegmund. Elisabet Swid possesses blazing full-throttle high notes for an exciting Sieglinde, but her voice is deep and even throughout the range. The painful despairs of “Du bist der Lenz” (after its opening statement of ecstasy) were movingly sung, and her nightmares in Act II intense. Ain Auger sang a stern, dignified, malicious Hunding. The eight valkyrie sisters were passionate and well-schooled. Sir Andrew Davis led an urgent, highly dramatic reading of the score, with barking horns for Hunding’s hounds and vital woodwinds in the lush, romantic pages. It was a top-grade Walküre, to make any Wagnerian eager for the working-out of the rest of the cycle. Photo Cory Weaver

Turandot, Elektra and the Dyer’s Wife with equal success. The smoothness and glamour of her voice are comparable to its great size, and she can produce it on horseback or on her knees supplicating Wotan. The voice shines over the orchestra without losing its warmth. She is a supple actress, and portrays a tender Brünnhilde, sentimental about the twin lovers even before Siegmund has convinced her to defend them, far more timid than is usual when Wotan outlines her future as a mortal woman. Vocalism aside, the demigoddess was not her style, at least in Pountney’s conception. Eric Owens has graduated from Alberich to Wotan (schwarz-Alberich to licht-Alberich, one might say), and while not as imperial in scope as some Wotans, he compensates in his moments of brooding or uneasy reflecting, in which his dramatic choices are always of interest. It is a thoughtful, appealing performance, full of regret. Tanja Ariane Baumgartner’s ravishing low tones match him with a queenly, sympathetic Fricka, more distressed by Wotan’s clumsy plotting than outraged by his infidelity. The lovers are Brandon Jovanovich, whose dark tenor sound and anguished acting make him a most sympathetic Siegmund. Elisabet Swid possesses blazing full-throttle high notes for an exciting Sieglinde, but her voice is deep and even throughout the range. The painful despairs of “Du bist der Lenz” (after its opening statement of ecstasy) were movingly sung, and her nightmares in Act II intense. Ain Auger sang a stern, dignified, malicious Hunding. The eight valkyrie sisters were passionate and well-schooled. Sir Andrew Davis led an urgent, highly dramatic reading of the score, with barking horns for Hunding’s hounds and vital woodwinds in the lush, romantic pages. It was a top-grade Walküre, to make any Wagnerian eager for the working-out of the rest of the cycle. Photo Cory Weaver

Lyric Opera of Chicago: “Die Walküre”